Funeral

I'm en route to North Carolina from Seattle. There is a two year old behind me, stuck between his mother's legs and the back of my seat, and he keeps plowing his head into the back of my seat with surprising strength. Bam! Bam! Bam! Those little people and their giant heads, like weapons. It goes on for hours and I keep turning around and looking at the mother but she always just smiles with determined ignorance. Finally I start to say something and she interrupts me: "Oh, is he bothering you?" And I say weakly, totally pathetic, "Um, maybe he could just stop with the head thing?"

She gently asks him to stop, with a little too much room in her tone for him to refuse, in my opinion. Then she flashes me one of those searing just wait till you have kids looks, and the plane starts to shake very suddenly. We're flying through something, something bad enough that the drink service is halted, which always feels way more disappointing than it should feel, and also unfair because the first half of the air craft got to have their drinks and now the plane is going down and they'll have more of a chance of surviving, since they're all hydrated and we're not.

The turbulence is bad. I hang onto my arm rest and feel really really angry at whoever is responsible for all of this, the invisible hydraulics in the air and the trajectory of the plane and the geography of the country and everything else. I was actually looking forward to the cross-country flight, a few relaxing hours to sit still and read a book and not be bothered. Actually, I was really looking forward to this trip- a quick trip- three days, two of them full travel days, to my grandmother's funeral in Cleveland.

|

| The Wilderness Discoverer heads out to Alaska |

It gets worse.

Last Monday, some of my crew and I were hoisted away during the work day and taken into Ballard for a mandatory drug test. There were eight of us, and we had to go into that back room with the security guy one at a time. It took an hour and a half. I was the happiest I've been in a while, totally relaxed, sitting there with an Oprah magazine, mentally directing the others to pee slow. Make this last. When it was my turn, I did a quick overview of the space in the room- a tiny room with a nonflushing toilet and a sink with broken taps, no water- and just enough space for me to curl up on the floor and shut my eyes. If I wanted to. Which I did. I estimated how much time I'd have- ten minutes- maybe fifteen? Before the security guy pounded on the door. Fifteen golden minutes to myself.

I know how to work hard. I promise I do. But this life, this boat world, was dropped into my lap when I least expected it. I had a job, car, house, boyfriend, dog, routine, friends, plans. And then this offer happened, and I said yes, and suddenly I cannot keep up. I wake up at six, try and get the dog out for a few minutes, pack my things, stop for coffee, run out the door to Fisherman's terminal. Almost everybody else lives on the boat. They already left behind the aforementioned dog, boyfriend, car, house. I haven't yet.

I screech into a parking space on the harbor and run up the gangway with coffee in one hand and it's amazing how much can spill out of that little hole in the to-go cup. I forget about breakfast or brushing my hair, whatever it takes to get my ass onto that ship before the all-hands meeting at 7:30. Last week I went to the wrong ship and therefore was four minutes late getting to the correct ship and I got an extremely firm talking to by my captain. Being reprimanded by the captain of your ship is like being yelled at by the president, the chief of police and your mom all at once. I told this story to Lisa a few days later, recalling the whole scenario in horror in the back room of her work. "Did you cry?" She asked, eyes wide. "I would have cried."

I didn't cry. I think I left my body. Like a dying person who floats above their mangled, car-wrecked corpse on the side of the highway and feels peace. I felt peace because I was planning, with utmost certainty, to jump overboard and drown myself as soon as I got a moment to myself. I've never been yelled at before in my life- surely death was the only option.

The day ends after 6pm. Then I go home, to the moping dog, the half-packed house that needs a subletter, the car with the broken breaks that won't be fixed until October, and I run run run run from task to task, and late at night I drive across the city and shore up at Andrew's house and he makes me dinner and listens to my my tyraid, yet again, about how bad I am at everything. He's cooked me dinner three hundred times. I've cooked him dinner one time. I'm leaning on him hard.

In case you were wondering, I didn't do it. I didn't curl up on the bathroom floor like a demented person having an episode. But I could have. And that was thrilling.

|

| The view from my doorway |

The Fish on the Dock

There are two stories I could tell right now. The first one is the triumphant story where I sleep on the side of the road next to roaring Icicle creek, climb eight pitches up Orbit, take pictures of Andrew's bloody fingers at the summit, stand at the edge of the cliff in the cold wind and hike out by moonlight. The story that I like to tell, the one where I'm strong and energetic and healthy, falling asleep in the passenger seat as Andrew drives down I-90 in a torrential rainstorm, safe after yet another big adventure, bringing us back to a city brimming with everything familiar. The life that I've carved out just right.

I'm going to live aboard a boat, and soon we're heading to Southeast Alaska and I'll be there all summer leading kayak trips through Glacier Bay and being a medic and on the weekends, until we leave the harbor, I go on these huge climbing adventures.

You see? Look how I can word it so that everything sounds so perfect.

I'd rather tell it like that.

I'd rather not tell the second story at all, because I don't want anyone to know what a rough time I'm having, how terrible I am right now at my job, at my own life.

The second story is that one where I'm failing, flailing, flopping around- picture a single fish in a net on the dock- the one where I'm late to everything, where I get lost, literally lost, in the passageways in the ship and I'm scared of my own room because there are no windows and it's next to the engine room and it's loud. The part where I'm exhausted and overwhelmed and fantasizing about quitting and falling asleep during the expedition team meeting and crying in my car to Randal, and my tears are white with salt which means I'm very very dehydrated because I can't find the water on the ship. That story where I'm sea-sick when I'm on dry land and the world is constantly tipping around me and the dog sits alone in the house all day and it's back to sleeping pills at night.

The transition into boat world has been tough. It feels like hell. I'm fairly certain I'm not doing a good job at it, and I always do a good job. With everything. Except this. As it turns out, two full time lives is one too many.

One of our vessels, the Safari Spirit, burned down at the harbor last week, and the crew has been laid off or thrown in to a new job, a demotion by necessity, onto a new ship. The Safari Endeavour is still afloat, with a full crew working every hour of every day to get it ready for embarkation, and I should be so grateful that it was not my ship that burned. But all I can think is, if it had been, if I had been on the Spirit, I could go home, and crawl into bed, and go back to my normal life and nobody could blame me because my ship no longer existed.

Of course, I can always just gloss over it. Glossing is an art, like everything else, and I've mastered it. I've mastered the wild, envy-inducing elevator pitch of my life:I'm going to live aboard a boat, and soon we're heading to Southeast Alaska and I'll be there all summer leading kayak trips through Glacier Bay and being a medic and on the weekends, until we leave the harbor, I go on these huge climbing adventures.

You see? Look how I can word it so that everything sounds so perfect.

I'd rather tell it like that.

I'd rather not tell the second story at all, because I don't want anyone to know what a rough time I'm having, how terrible I am right now at my job, at my own life.

Alphabet Rock

It Will Bite You

I am amazed at how quickly everything is happening. The background checks and all the paperwork are over. I sat in the dining room of the boat and filled out chart after chart, line after line, detailing every medical event that's ever transpired in my life. It was the most fun ever, and I say that with sincerity. It's like a tiny, compact autobiography of trauma.

My answer: Frostbite and Hypothermia. (What I wanted to write was Frostbite!!! And HYPOTHERMIA!!!! But I kept it cool.) (Ha!)

Have you ever been hospitalized for a cold-weather related injury or illness?

Frostbite and Hypothermia.

Have you ever experienced sea-sickness? I chewed on the pen cap and studied my options: No. Yes. I don't know.

I checked the little box next to I don't Know.

We'll Soon Find Out would have been my best answer.

I found a subletter for my place over the summer. I found a good home for my dog, just for the summer, with two people I trust more than I trust myself. I put my two weeks notice in at the Seattle Boulder Project where I work. Where I used to work. It was the most fun ever, and I say that with sincerity. I'll miss that place.

Ooh, but I get to be the Medical Person In Charge, so that will be great fun!

My to-do list is growing as fast as I can cross things off. All these bright, inviting little restaurants are opening on Ballard Ave and I can't pass one without texting Andrew: We've got to go there before I leave! Like NOW! Like TONIGHT!

Everyone who has ever been to South East Alaska gets this look in their eye when they find out that's where I'm going for the summer. It will bite you, they all say, the way it bit me. And you'll never get it out of your system. I believe them. I believed the CEO of Intersea Discoveries when he told us we'd never, ever be the same after setting foot in Alaska. It was easy to take his word for it because he was crying as he delivered his welcome speech. He was crying as he recounted his first trip to Alaska some thirty years prior, when he admitted how much fuel our fleet of seven boats would use over the course of three months. "Do we have to use the fuel? Yes, we do. Are we going to spill any into the sea?" He stopped and put his hands above him like a preacher. "God Forbid. God Forbid."

And so I know my whole world is about to expand and all that. I know, and I know that I can't know the extent of it. But at the same time, in this funny and fantastic dichotomy, my physical world is actually about to shrink. To the size of a small boat called The Safari Endeavor. And I am not going to be able to run. I won't even be able to walk quickly. So for now, I'm running. I'm speeding all over the place. (On foot. I drive very carefully.)

Each night I pull the dog into bed and tell her about my day. Then I tell her I'll be leaving, but by Autumn I'll be back. And I'll have something that I've never really had before, when I get back. I tell her. This may come as a shock, babe, but when I come back, I'll have gained something really important.

Money.

How Weather Works in Paradise

Our first day back was so long awaited. We spent the season inhaling chalk dust and ripping up our fingers on gritty, neon plastic holds, lying on our backs at the Seattle Bouldering Project and daydreaming about the day we could be released from our winter confinement. About the day the rain would stop, and the sun would beat down on the rocks throughout Washington and we could once again spend every hour of daylight inching up their warm, dry faces. I live in a city that is wet for six months out of the year, and by the end of that sixth month, the idea of dry anything feels like pure fantasy. The concept of dry, sun-warmed rock seems so remote it's almost cruel.

Then the weather flipped upside down onto its head, and all of a sudden I was sitting at the base of the Lower Town Wall in Index with Andrew, hiding from the sun, and we were both covered in sweat and completely shell shocked. What is that thing in the sky? Why is it burning my skin? Why am I so thirsty?

In my rain daze, I'd forgotten that sunny weather isn't all pleasantly warm rock and gentle breezes. We were a few pitches up on the sun-exposed face, just above the shady, sheltering pine trees, and that burning orb in the sky was scorching the strength right out of me. After we rapped back to earth we slunk around for a while, looking for the next route, eventually retreating to the base of the rock where there was a slice of shadow and refrigerated air leaking from the cracks. Why is that bright thing making me feel sleepy?

Oh my God, in this city and its monotonous climate I've forgotten how weather works.

Our first day back was the beginning of April. It was cold in the shade but the rock was dry. We climbed a three pitch classic called Rattletale. On the second pitch, I discovered something new about myself. I don't actually know how to climb crack. I've been climbing now for 16 years so I just assumed I could catch on, but crack climbing is completely different than everything else. It's like a different sport. When I daydream about climbing, I think about clean faces, catching a tiny lace-thin protrusion for your toe, gripping little chips with your fingers. Either that or giant, pumpy overhangs with holds like buckets. But not crack.

Not this junk show of jamming and and locking twisting and wrenching, tape and dirt and blood and skinned hands. I don't physically know how to do this, I realized, which is a bit alarming when you're already two pitches up. I scratched my head and thought about what to do next. Then I lay-backed the whole thing, which is essentially like looking at a big, beautiful, bouncy rapid and deciding to take the exhausting, rocky sneak route on the left and hope that nobody sees you. (Which I'm also really good at doing.)

But Andrew caught me. And the next weekend we were back at Index, doing laps on the easy crack at lower town wall as he patiently showed me, move by move, the proper crack climbing technique. Because our plans before I go to Alaska involve cramming a summer's worth of big wall and trad into a few short weeks, and there's only so much lay back and sneak routes and faking it a girl can do before she needs to nut up and learn how to jam.

I'd like to point out, just for the record, that after the sun fell behind the cliffs and the day cooled around us, we started to function again. Andrew put up the most inspired lead I've ever seen, a really effing hard route called Zoom, and I was able to follow him, and we were redeemed. And on the walk back to the car on the train tracks, in a tunnel of trees and their new, light-green leaves, I was reminded that we live in Paradise. There are many places of Paradise around the world and this is one of them. And so was the hole in the wall Mexican place we found on the way home.

Then again, maybe Paradise has less to do with where you are and what you're doing, and everything to do with who you're with. Who knows? I don't know such things.

Then the weather flipped upside down onto its head, and all of a sudden I was sitting at the base of the Lower Town Wall in Index with Andrew, hiding from the sun, and we were both covered in sweat and completely shell shocked. What is that thing in the sky? Why is it burning my skin? Why am I so thirsty?

In my rain daze, I'd forgotten that sunny weather isn't all pleasantly warm rock and gentle breezes. We were a few pitches up on the sun-exposed face, just above the shady, sheltering pine trees, and that burning orb in the sky was scorching the strength right out of me. After we rapped back to earth we slunk around for a while, looking for the next route, eventually retreating to the base of the rock where there was a slice of shadow and refrigerated air leaking from the cracks. Why is that bright thing making me feel sleepy?

Oh my God, in this city and its monotonous climate I've forgotten how weather works.

Our first day back was the beginning of April. It was cold in the shade but the rock was dry. We climbed a three pitch classic called Rattletale. On the second pitch, I discovered something new about myself. I don't actually know how to climb crack. I've been climbing now for 16 years so I just assumed I could catch on, but crack climbing is completely different than everything else. It's like a different sport. When I daydream about climbing, I think about clean faces, catching a tiny lace-thin protrusion for your toe, gripping little chips with your fingers. Either that or giant, pumpy overhangs with holds like buckets. But not crack.

|

| Smith Rock Face: Daydream Material |

|

| Layback Technique, aka Not crack climbing. |

I'd like to point out, just for the record, that after the sun fell behind the cliffs and the day cooled around us, we started to function again. Andrew put up the most inspired lead I've ever seen, a really effing hard route called Zoom, and I was able to follow him, and we were redeemed. And on the walk back to the car on the train tracks, in a tunnel of trees and their new, light-green leaves, I was reminded that we live in Paradise. There are many places of Paradise around the world and this is one of them. And so was the hole in the wall Mexican place we found on the way home.

Then again, maybe Paradise has less to do with where you are and what you're doing, and everything to do with who you're with. Who knows? I don't know such things.

Heading Home

Everywhere I go

Big, bold, bright, beautiful, buoyant boat world.

Randall: "I'll take you to buy your first pair of Xtra Tufs. It will be a ritual. You'll be knighted."

Randall and I are on separate ships, in and out of Juneau on different days. We will literally be ships passing in night. Passing in the night through Glacier Bay.

"We won't see each other."

I frowned.

"Never?"

"We can wave from the deck. We can have our own radio station. We can speak in code."

"Is the spring beautiful this year?"

"Everything looks beautiful when you're about to go away."

We'll miss you, Ty. We wish you were coming on board. It will feel strange without you.

You know what else will feel strange? 12 weeks without alcohol. We'd better pour it down right here and right now.

Randall: "I'll take you to buy your first pair of Xtra Tufs. It will be a ritual. You'll be knighted."

Randall and I are on separate ships, in and out of Juneau on different days. We will literally be ships passing in night. Passing in the night through Glacier Bay.

"We won't see each other."

I frowned.

"Never?"

"We can wave from the deck. We can have our own radio station. We can speak in code."

"Is the spring beautiful this year?"

"Everything looks beautiful when you're about to go away."

We'll miss you, Ty. We wish you were coming on board. It will feel strange without you.

You know what else will feel strange? 12 weeks without alcohol. We'd better pour it down right here and right now.

I met my expedition leader. We took a walk through the harbor. I went to Boat training this week: Bear safety and story telling lectures. I learned that when you are fighting with a bear, you are fighting for your life.

When you're telling a story, you are also fighting for your life.

But I already knew that.

I broke the news to my dog. "I'll be thinking of you when I'm at sea."

"Just because you're living on a boat doesn't mean you're going out to sea. Get me another beer."

She takes things in stride. In general, she is better at life than I am.

Boat World Begins

I came home from my EMT course and felt dizzy. Leavenworth had been a place of heavy snow and deep concentration. Seattle, in the full bloom of a warm, green spring, was more complicated. I studied, I unpacked and slept late and paid for coffee with change I found in handfuls around the house. I deeply missed that temporary world where all that existed was text books and fake trauma, broken up by Friday evenings at Icicle and quick runs down the frozen dirt road.

But I started climbing again, and took the dog to the beach, ate at good restaurants on weeknights, and sank back into normal life.

And then what? In an expensive city where it's notoriously difficult to crack into the EMS world. Me with so little experience. Then what?

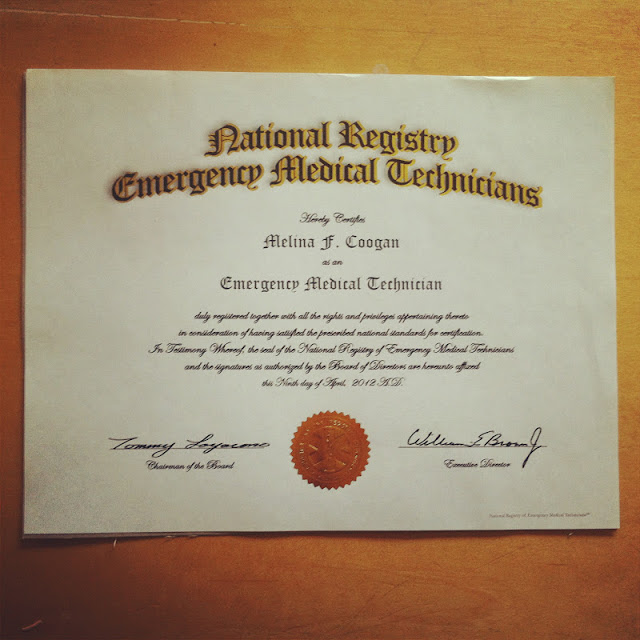

But it started to feel better as the days passed. I studied and passed and my certificate came in the mail with its official golden seal. I bought food for the house, started to function as a normal person again, and kept climbing.

Climbing. That was the answer. That was where my momentum lay. We started to plan big things for the summer. I'd go to Haiti for a week and then come home and get on big walls. Smith, Squamish, Red Rocks, Leavenworth. Liberty Crack. As each warm day gave way to the next, the idea of a summer of road trips and after work sunset trips to the exits started to appeal to me more and more. I was begging for weekends off at the climbing gym. We were studying guidebooks, driving up Highway 2, jamming tape-gloved hands into cracks in Index three pitches up.

And then, one soft Tuesday night, only a few days after I passed the NREMT, the phone rang.

And in thirty seconds, life tipped and all of those plans slid off the end table. I was offered a job, on a boat, working as a guide in the harbors and mountains around Juneau, Alaska.

I had not applied for the job. I'd spent a few good, hard nights in Ballard with Randall and a few of his friends from the adventure cruises in Alaska. We drank a lot of beer and played pool and I listened to the stories they told of the weird, magical, transient lives of Boat World.

Then one time, Randall sat down next to me at a bar called The Loft leaned his shoulder against mine and said, "They love you, Melina. My friends from boat world."

I think it was the next day that I was offered a last minute spot on a boat.

A few days after the phone call, I went down to Fisherman's terminal on a bright Friday morning and met with the captain of my ship. We talked a little about guiding, storytelling, poetry. I said I just happened to be a registered MPIC- Medical Person In Charge for expeditions and sea vessels, would I be able to use those skills this summer? She assured me that I would. Then she offered me the job. I took it.

My ship, the Safari Endeavor, is leaving the Harbor on May 27th and I'll be on it, in a berth below the water line with no windows and a stranger sleeping in the narrow bed next to me.

Just like that, I joined Boat World.

Sometimes I think this writing is magic. Just two posts ago, I wrote that I wanted my life to have ships and medicine. Now I have both.

But I started climbing again, and took the dog to the beach, ate at good restaurants on weeknights, and sank back into normal life.

And I was grateful to be home but I wanted something. Some thing. I wanted momentum, to keep flinging ahead at the same pace I'd kept in Leavenworth. Up early, alert for every moment of class, aware that I was always one missed chapter, one poorly timed daydream away from not passing. I desperately wanted to keep every inch of my life as vital and necessary as they had been the past five weeks. I wanted to work in medicine.

Okay, I thought, while running my laps, or in the shower, or stuck in traffic, or walking the dog, or boiling water, or in the middle of the night, so I'll go to Haiti. As soon as I'm registered, I will book a trip to Haiti.

But it started to feel better as the days passed. I studied and passed and my certificate came in the mail with its official golden seal. I bought food for the house, started to function as a normal person again, and kept climbing.

Climbing. That was the answer. That was where my momentum lay. We started to plan big things for the summer. I'd go to Haiti for a week and then come home and get on big walls. Smith, Squamish, Red Rocks, Leavenworth. Liberty Crack. As each warm day gave way to the next, the idea of a summer of road trips and after work sunset trips to the exits started to appeal to me more and more. I was begging for weekends off at the climbing gym. We were studying guidebooks, driving up Highway 2, jamming tape-gloved hands into cracks in Index three pitches up.

And then, one soft Tuesday night, only a few days after I passed the NREMT, the phone rang.

And in thirty seconds, life tipped and all of those plans slid off the end table. I was offered a job, on a boat, working as a guide in the harbors and mountains around Juneau, Alaska.

I had not applied for the job. I'd spent a few good, hard nights in Ballard with Randall and a few of his friends from the adventure cruises in Alaska. We drank a lot of beer and played pool and I listened to the stories they told of the weird, magical, transient lives of Boat World.

Then one time, Randall sat down next to me at a bar called The Loft leaned his shoulder against mine and said, "They love you, Melina. My friends from boat world."

I think it was the next day that I was offered a last minute spot on a boat.

A few days after the phone call, I went down to Fisherman's terminal on a bright Friday morning and met with the captain of my ship. We talked a little about guiding, storytelling, poetry. I said I just happened to be a registered MPIC- Medical Person In Charge for expeditions and sea vessels, would I be able to use those skills this summer? She assured me that I would. Then she offered me the job. I took it.

My ship, the Safari Endeavor, is leaving the Harbor on May 27th and I'll be on it, in a berth below the water line with no windows and a stranger sleeping in the narrow bed next to me.

Just like that, I joined Boat World.

Sometimes I think this writing is magic. Just two posts ago, I wrote that I wanted my life to have ships and medicine. Now I have both.

|

| my new home |

Hey now, time to keep moving

Nationally Registered

I passed the National Registry Exam. That makes me a Nationally Registered EMT. I have a certificate that will expire in 720 days unless I keep up with ongoing education requirements. That's how you find out that you passed, by the way. You sign into your profile in the NERMT website and it says, "Your certificate will become inactive in 720 days unless you do all this stuff." No "Congratulations," no "That test was weird, wasn't it! But nice job, welcome to the club."

The test was weird. I think there are people who know EMS and people who know how to write comprehensible test questions and never the two shall meet. In my week of pure studying that led up to the exam, not to mention the month of live-eat-breathe EMS that came first, I was starting to feel pretty good about my chances of passing. And while I got overwhelming support from everyone around me, a paramedic friend of mine kept warning me that the test would be...odd. "You'll do great," he'd say. "You'll pass. But it's....odd. You'll walk away from it cross-eyed. That's normal."

Actually, it was infuriating. I hated the test. And I generally love tests. "An opportunity to celebrate your knowledge!" Our instructor would joke as he handed out the difficult RMI tests during the course, and while everyone groaned I'd be bouncing around in my seat thinking, hell yeah! Celebrate!

But the exam was killer. Each question seemed more unduly complex and vague than the last. This is how you're assessing our knowledge? All that wonderful knowledge inside my head carefully bestowed on us by hardworking instructors and this is how you're assessing me? A) Sterile dressing or B)Direct pressure? What about Direct Pressure with sterile dressing, where is that answer? I held my breath as I banged my finger against the mouse, clicked my way through 70 questions (some people got 150 questions, I got 70) and then the woman working at the test center, who by the way was exactly two feet tall, handed me a certificate that I'd taken the thing and that was that.

And afterwards there was no one to go to Icicle with and blow off steam. The whole thing felt very anti-climactic. And for the first time in my life, I had absolutely no idea whether or not I'd passed the exam. On the long drive home from Everett, I called Ty and vented my frustration in a manner that sounded high-pitched, like stridor. It sounded a lot like whining. I don't normally whine about things. "The worst part," I told him, "Is that if I do fail, I'll have no idea what to study for next time."

Ty kept saying "Aw geez."

"Aw Geez, Melina, that doesn't sound good at all."

We went to see Radiohead that night at the Key Arena. Just as an aside, there are more than 18,000 seats in the Key Arena, and yet we still end up seated directly behind my ex-boyfriend Ben, the one I've written about so often here, and his fiance. Eighteen thousand seats. Go figure.

I told them I'd just passed the NREMT. Screw it. When you're faced with the prospect of staring at the back of your ex-boyfriend's head all evening, you've got to say something fiercely confident and cool. None of this, "Ah I took this test thing and it had my way with me and I got to the testing center 15 minutes late because google maps blows and I'm not really sure what happened after that and the proctor was a midget, but, like, the smallest midget I'd ever seen, I hope I didn't stare."

Nah. You've got to be all, "Hey, dude, you get fucked up tonight, I've got your back."

Which also sounds better than, "Hey, when you get old and present with symptoms that call for Nitro, and you have your own prescription, I will help assist you with that, but only after calling Medical Control for permission, unless it is expressly worded in my protocol."

Then the lights went down, and Radiohead started, and I was actually able to relax. If you're an extremely impatient person like I am, and you're waiting to hear back about whether or not you're officially an Emergency Medical Technician, I recommend going to see Radiohead. All the lights and sound and people. I stopped thinking entirely.

And in the morning I raced out of bed, kicking the covers into pile on the floor and checked my phone. On the website, there was a message telling me I'd been assigned a number, and that I'd better get on my continuing education or I'd lose my NREMT status. Still not entirely sure, I clicked through the whole site, on that tiny little screen, and eventually found a little note that said oh yeah, you passed the test.

That weird test.

Somehow, there in the mountains in the snow, in the midst of all those wonderfully distracting people, I managed to learn everything I needed to learn.

The test was weird. I think there are people who know EMS and people who know how to write comprehensible test questions and never the two shall meet. In my week of pure studying that led up to the exam, not to mention the month of live-eat-breathe EMS that came first, I was starting to feel pretty good about my chances of passing. And while I got overwhelming support from everyone around me, a paramedic friend of mine kept warning me that the test would be...odd. "You'll do great," he'd say. "You'll pass. But it's....odd. You'll walk away from it cross-eyed. That's normal."

Actually, it was infuriating. I hated the test. And I generally love tests. "An opportunity to celebrate your knowledge!" Our instructor would joke as he handed out the difficult RMI tests during the course, and while everyone groaned I'd be bouncing around in my seat thinking, hell yeah! Celebrate!

But the exam was killer. Each question seemed more unduly complex and vague than the last. This is how you're assessing our knowledge? All that wonderful knowledge inside my head carefully bestowed on us by hardworking instructors and this is how you're assessing me? A) Sterile dressing or B)Direct pressure? What about Direct Pressure with sterile dressing, where is that answer? I held my breath as I banged my finger against the mouse, clicked my way through 70 questions (some people got 150 questions, I got 70) and then the woman working at the test center, who by the way was exactly two feet tall, handed me a certificate that I'd taken the thing and that was that.

And afterwards there was no one to go to Icicle with and blow off steam. The whole thing felt very anti-climactic. And for the first time in my life, I had absolutely no idea whether or not I'd passed the exam. On the long drive home from Everett, I called Ty and vented my frustration in a manner that sounded high-pitched, like stridor. It sounded a lot like whining. I don't normally whine about things. "The worst part," I told him, "Is that if I do fail, I'll have no idea what to study for next time."

Ty kept saying "Aw geez."

"Aw Geez, Melina, that doesn't sound good at all."

We went to see Radiohead that night at the Key Arena. Just as an aside, there are more than 18,000 seats in the Key Arena, and yet we still end up seated directly behind my ex-boyfriend Ben, the one I've written about so often here, and his fiance. Eighteen thousand seats. Go figure.

I told them I'd just passed the NREMT. Screw it. When you're faced with the prospect of staring at the back of your ex-boyfriend's head all evening, you've got to say something fiercely confident and cool. None of this, "Ah I took this test thing and it had my way with me and I got to the testing center 15 minutes late because google maps blows and I'm not really sure what happened after that and the proctor was a midget, but, like, the smallest midget I'd ever seen, I hope I didn't stare."

Nah. You've got to be all, "Hey, dude, you get fucked up tonight, I've got your back."

Which also sounds better than, "Hey, when you get old and present with symptoms that call for Nitro, and you have your own prescription, I will help assist you with that, but only after calling Medical Control for permission, unless it is expressly worded in my protocol."

Then the lights went down, and Radiohead started, and I was actually able to relax. If you're an extremely impatient person like I am, and you're waiting to hear back about whether or not you're officially an Emergency Medical Technician, I recommend going to see Radiohead. All the lights and sound and people. I stopped thinking entirely.

And in the morning I raced out of bed, kicking the covers into pile on the floor and checked my phone. On the website, there was a message telling me I'd been assigned a number, and that I'd better get on my continuing education or I'd lose my NREMT status. Still not entirely sure, I clicked through the whole site, on that tiny little screen, and eventually found a little note that said oh yeah, you passed the test.

That weird test.

Somehow, there in the mountains in the snow, in the midst of all those wonderfully distracting people, I managed to learn everything I needed to learn.

Crushing and Coding

I stayed on the homefront the weekend. Still unpacking, somehow, from the month away. Still studying. Still getting my bearings back in the city. That has included a lot of running. Miles and miles every day. What the hell? I'm not a runner. I've railed against running since I was forced to walk the miserable mile death march in 7th grade. But something about medicine, all the new people and the numbers and the acronyms, every part of this frightening and fascinating new path I've been shot onto, I feel like I'm filled up with gasoline and every new passing thought is a match.

I started running down the cold, beautiful mountain road in Leavenworth after class every day just to get an hour by myself, to have a few moments to think about what in the world I was doing out there, if I was going in the right direction. If crushing down on on a man's chest who coded in the middle of a casino was something I wanted to do on a daily basis. I decided it was.

I also decided I sort of liked running. I'd never choose it over a day on the river or on the rock, but I like that I can do it whenever, and all by myself.

****

We celebrated spring last night with the official Ballard Margarita Tour 2012. A combination of EMS and Boat world people. We got along just fine.

Ballard on a sunny Saturday evening, the first warm day of the year. We were brave just to venture out.

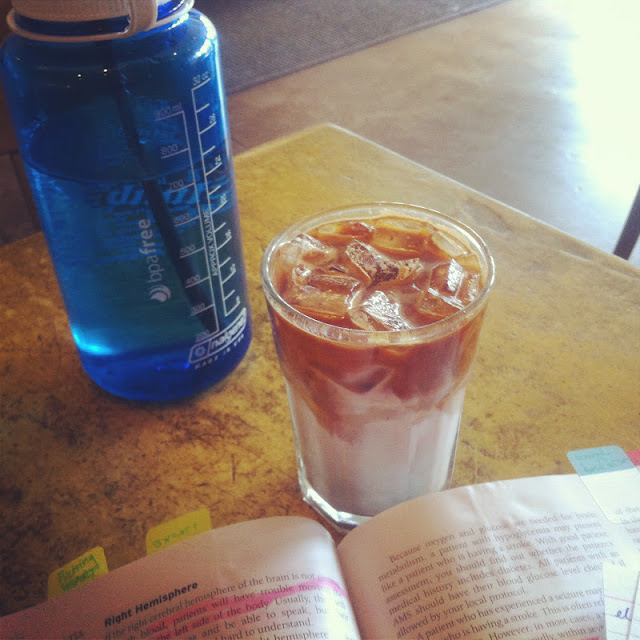

Today it's Easter, so they tell me. In the grand tradition of this Holiday, I'm having brunch. A liquid brunch of espresso, music, highlighters and once again, the chapter on the airway. I love this. I want so much more of it.

And it's warm. Warm enough. This picture proves it.

Happy Easter, y'all! Hope you are outside somewhere, with somebody you love, and a dog, studying something that makes you, in equal parts, want to fall in love and want to vomit.

Ships and Medicine

Yesterday evening, Ty and I met Randall in the cluttered, creaking harbor of Fisherman's terminal. Randall lives there, for now, aboard a boat that in five weeks will make its slow way up to Alaska till the end of summer. He met us standing on the deck of his ship with his familiar checked flannel and slow, bright smile, the smile that always makes him appear like he's laughing at something just beyond our line of vision.

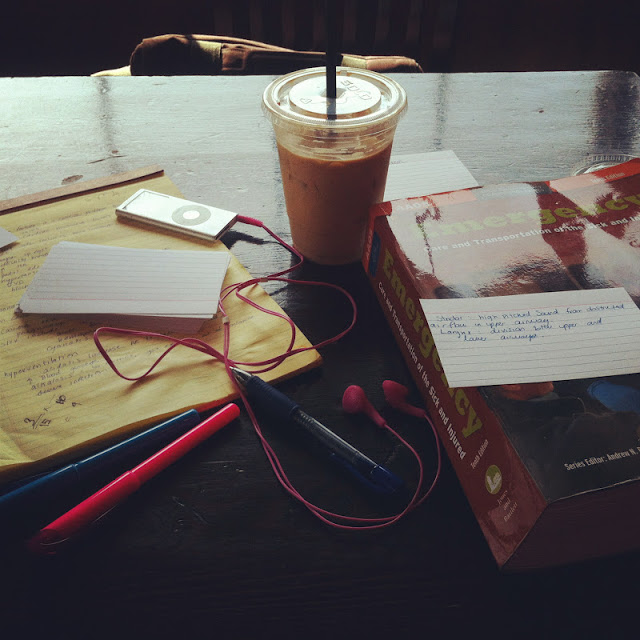

The three of us were supposed to meet up and study for our national EMT registry exam, but the strange, steadily undulating world of the harbor drew us in. Pale Ale and stories of a life guiding off of the rugged Alaskan coast and living in a berth beneath the water line easily stole our attention from our massive text books.

And in the End, Ty and I walked away feeling rather landlocked. Even with everything we've got going on, even being permanent residents of my favorite city on Earth. We both want something more. We both want Sea Change.

I want ships and medicine.

But first, we have to pass this exam. So for now we settled for a Ballard coffee shop and a few more hours of quizzing each other on the Glasgow Coma scale and all the endless acronyms.

The three of us were supposed to meet up and study for our national EMT registry exam, but the strange, steadily undulating world of the harbor drew us in. Pale Ale and stories of a life guiding off of the rugged Alaskan coast and living in a berth beneath the water line easily stole our attention from our massive text books.

And in the End, Ty and I walked away feeling rather landlocked. Even with everything we've got going on, even being permanent residents of my favorite city on Earth. We both want something more. We both want Sea Change.

I want ships and medicine.

But first, we have to pass this exam. So for now we settled for a Ballard coffee shop and a few more hours of quizzing each other on the Glasgow Coma scale and all the endless acronyms.

Absentia

I've been an absent pulse on this blog lately. That's because I've been studying, and studying, and studying for the National EMT registry exam that I'm going to take in a few days. I'm not just cramming to pass, though. I want to know this stuff, on a level way below tissue. There is only so much about EMS that I can understand before I actually start practicing in the field, but of that limited knowledge, I want to know everything.

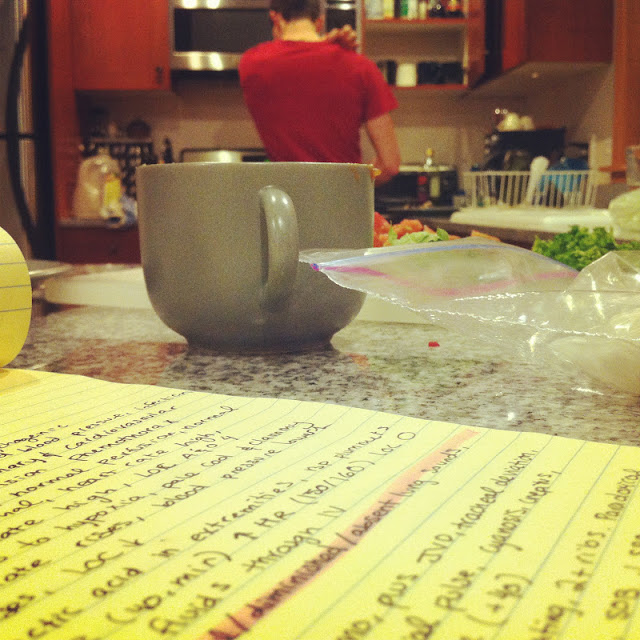

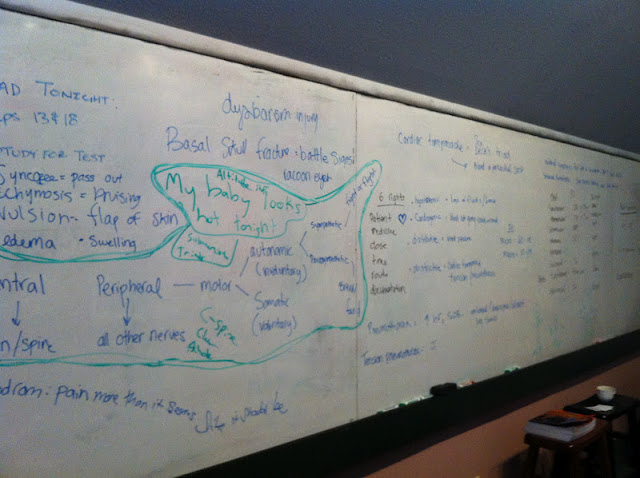

As eager as I am to get this exam over with, to get my certificate in the mail and be a fully certified EMT, I like studying. I love writing out endless acronyms and knowing exactly what they mean, where they'd come into play, how I'd go about assessing them in a patient. I like the butterfly loops of blood through the heart and lungs. Mostly, though, I like being able to just sit there and do nothing but read, and make no decisions, and answer to nobody, and watch the uncertain spring outside the window flicker between cold rain and weak sun. Sometimes, as a break, I'll put my head onto the table, close my eyes and picture myself back in the deep snow and quiet of Leavenworth, or back at the noisy classroom on a late night with my friends, writing endless lines of notes on the board and becoming loopy from sugar, sleeplessness and what we termed Acute Acronym Overload (AAO).

For the last few days, my house in Seattle served as the halfway home for my EMT friends as they waited to take their exams.

As eager as I am to get this exam over with, to get my certificate in the mail and be a fully certified EMT, I like studying. I love writing out endless acronyms and knowing exactly what they mean, where they'd come into play, how I'd go about assessing them in a patient. I like the butterfly loops of blood through the heart and lungs. Mostly, though, I like being able to just sit there and do nothing but read, and make no decisions, and answer to nobody, and watch the uncertain spring outside the window flicker between cold rain and weak sun. Sometimes, as a break, I'll put my head onto the table, close my eyes and picture myself back in the deep snow and quiet of Leavenworth, or back at the noisy classroom on a late night with my friends, writing endless lines of notes on the board and becoming loopy from sugar, sleeplessness and what we termed Acute Acronym Overload (AAO).

For the last few days, my house in Seattle served as the halfway home for my EMT friends as they waited to take their exams.

They got a handful of deceivingly sunny days, beaches and breakfasts and everything we figured we deserved.

Each one of them remarked on what a gorgeous life I have. The beautiful wooden house in the garden, good friends all over town and the days of climbing and writing and running around. And I told them I knew I was lucky, that I'd built this life here on the West coast for the past ten years. But knowing what I know about EMS and the way it's run in Seattle, and the sorts of things I want to with my training and career, places I know I want to go, and starting from down here at the very bottom, it seems likely that I'll have to choose between this picturesque but unsustainable life in the city and starting over somewhere new. Pulling away from all of it. And that's when I started studying, so I didn't have to think about it any more.Click

Tachycardic

For my 27th birthday I got a plane crash in the woods. I got a growler of Icicle Beer left on my doorstep from a group of boys whose arms I use as a pincushion for my shaky IV sticks, and a foil balloon from a quiet boy who was raised inside of a cult in Texas. I got an Alaskan paramedic smiling as he handed me a plate of chocolate, lit up with candles, a room full of huge ex-marines and special agents and arctic mountain guides dressed in long underwear singing to me and raising bottles of Icicle's double porter. And I got a huge, fat-flaked snow storm that lasted for days.

Not a bad start.Hell, it's everything I ever wanted.

The gratitude I feel at being here, at being twenty seven years old and having done everything I've done and now being in this place, learning these skills, is utterly overwhelming. I wake up in the middle of the night aware that my brain, in my unconscious state, is quietly and meticulously reviewing everything I learned the previous day. It's three in the morning and I wake up whispering the Glasgow Coma scale and oxygen flow rates. I can run much longer and much faster than I do at home, which isn't saying too much, but it is saying something. Every new person I've met, every moment spent on the ridge in the snow at night monitoring someones broken body for signs of shock, every tracing of the blood's path through the heart and lungs, every word that leaves my instructors mouth becomes fuel for me, a combination of motivation and inspiration and fear and adrenaline. I feel like I've been gunning the engine for weeks, but I can't actually go anywhere until I've passed all the exams. It's building up, an ever increasing pressure inside my vessels. My respiratory rate is increasing. My pulse rate is hummingbird high.

I feel like I'm coming apart at the seems, as if my body is no longer a sufficient vessel for everything I'm coming to understand. I would not be surprised if, one day this week, I stood up at my desk and split cleanly apart, floated away. If I can keep my hands in time with my head, ensure that they are able to work the ropes and the needles and tubes as fast and easily as my brain can see it all written out in front of me, if I can run as fast as my heart rate, and if somehow I can someone manage to voice the things inside that need to be said, pure and exact and nothing more, if my physical actions are as focused and direct as my mind is quick, then I have a chance at staying whole.

Late Twenties? How.....?

Harden up

Just a disclaimer- while I'm up in Leavenworth taking this course, I won't be able to write well. I don't have the time or the internet capabilities. There is a lot of crazy stuff going on, and I hope later on I'll get the chance to write out all the stories in a decent manner. For now, here is is in the raw:

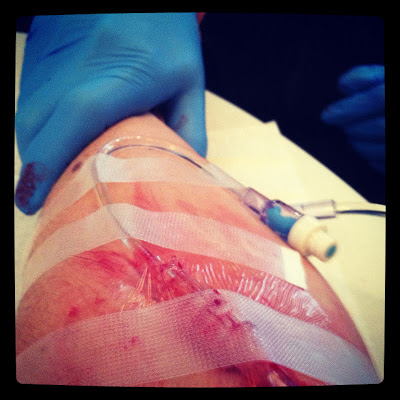

They told us that every class, they have one or two go down during IV training.

It wasn't me, but it would have been if it had lasted any longer. My friend brushed his fingers over the vein on the inside of my arm, stuck it with a needle then pushed three inches of white tube inside it. It took a while, because of all those little meticulous steps it takes to push the catheter fully into the vein, and because it was the first time for all of us. Our instructor hovered over him- "That's right- no, not like that, don't pull the needle back, push with your index finger- wait, just wait there for a sec-" as I studied the whole apparatus intently, knowing I'd have to do it next. It kept going and going, and I looked away, and a few feet away a boy standing by the kitchen started to get blurry. I lolled my head against somebody's chest and then it was over, and thing was in and they hooked in the fluid bag. There was plenty of blood.

Still, it was much easier to take the stick than to give it. I stuck both of Randall's arms and failed both time, and when he gasped with the pain it was difficult not to withdraw the needle and pull away. I managed to get it in the third time after I'd worn out his veins and moved on to another victim.

That's a big lesson we're learning- how to fix people temporarily, enough to get them onto a back board and onto an ambulance. We're not exactly learning how to ease their pain- some situations, certainly, but treatment for us does not always mean relief, it means stabilizing. When we straighten broken limbs and drag them forward by the arms and roll busted up people onto their side to palpate their back, it hurts. And if I withdraw in response to their pain, I'll just have to do it again. It's against my every impulse. Harden the fuck up, is what they say around here.

That's a big lesson we're learning- how to fix people temporarily, enough to get them onto a back board and onto an ambulance. We're not exactly learning how to ease their pain- some situations, certainly, but treatment for us does not always mean relief, it means stabilizing. When we straighten broken limbs and drag them forward by the arms and roll busted up people onto their side to palpate their back, it hurts. And if I withdraw in response to their pain, I'll just have to do it again. It's against my every impulse. Harden the fuck up, is what they say around here.

The process of hardening the fuck up is fucking hard.

The place where we recover

The place where things are learned

Four chambers of the heart

I have one shred of internet.

This time in my life is surreal. Our lodgings are so tranquil and removed, wooden houses settled into deep snow on a road of thick ice and frozen mud, the gold-floored yurt, a tree house, a hot tub in with a view of starlight through tall pines. The surrounding is in such stark contrast to what we are learning every day, the photos of brain matter and split skulls and shattered windshields.

We run into the woods carrying oxygen tanks during the day, finding our patients crumpled around trees, breathing rapidly with sucking chest wounds painted on with thick make up, and it's incredible how fast all our ABCs and patient assessment triangles evaporate. In the classroom I can carefully pen out what each of the DCAPBTLS stands for, but when I'm faced with a broken spine and dropping blood pressure- a fake broken spine and staged dropping blood pressure- I don't know what to do. Or, more accurately, I know what to do but I can't remember which order to do it in.

Here's why it's so surreal. Because everything we do during the week is staged, but on the weekends it becomes real. Two of the boys took the first clinical rounds last night, Friday night, as the rest of us were out in Leavenworth drinking beer in front of the outdoor fire at Icicle brewery. They returned early in the morning and we saw them over breakfast. They were pale and excited. They'd had a gun shot to the head and a full hospital lock down. They described seeing brain matter, blood, massive amounts of cerebral spinal fluid. They told about seeing his vitals drop and his blood pressure drop to nothing, and then they had to cut the clothes off of the corpse. They described hearing the family screaming in the waiting room, a gang fight that subsequently broke out and the endless amounts of cops streaming in and out. There was also a car crash, but that took the back burner in terms of excitement.

Meanwhile, we soaked in the hot tub in the fresh, chilled mountain air, fell asleep in our clean beds, and waited for our turn.

Surreal.

It's a funny mix we've got here in the woods. Late the other night, cramming for our first big exam, the FBI agent and the nuclear submarine man patiently went over the respiration process and the four chambers of the heart with me, over and over. Yesterday, Libby and I killed Tate many times over as he slipped into shock and we forgot his blood pressure, forgot to regulate his temperature and almost strangled him with a cervical collar. Girls are a rare commodity around here. When I go into town, I put my grandmother's opal ring on my left ring finger. Yesterday night at the bar in Leavenworth, a young man was asking over and over, "Where are you from? What are you doing here?" over and over, so much so that we thought he might have a head wound. And then he leaned closer and whispered, "I know how old you are. You're 23....going on sexy." My friend Tate, recognizing my symptoms of distress, draped his arm around me and said coolly, "I see you've met my wife?" I smiled, leaned into him, and flashed my left hand to the boy with the would-be head wound.

Later on, as we were leaving, a boy almost barreled me over he ran full speed down the empty street. Then, a few ahead, he tripped and fell flat upon his face, arms splayed, and lay still. Alright! I said to myself. Go time! "Are you okay?" I yelled, running to his side. But then my patient, my very first patient, jumped up with a startled look and a bloody nose, and kept on running.

Which is exactly how I've felt the past week. Disoriented, unsure of my footing, running, going somewhere, going very fast.